Putting the social into health care

- Leanne Wells

- Feb 4, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Feb 22, 2025

Leanne Wells and Paresh Dawda

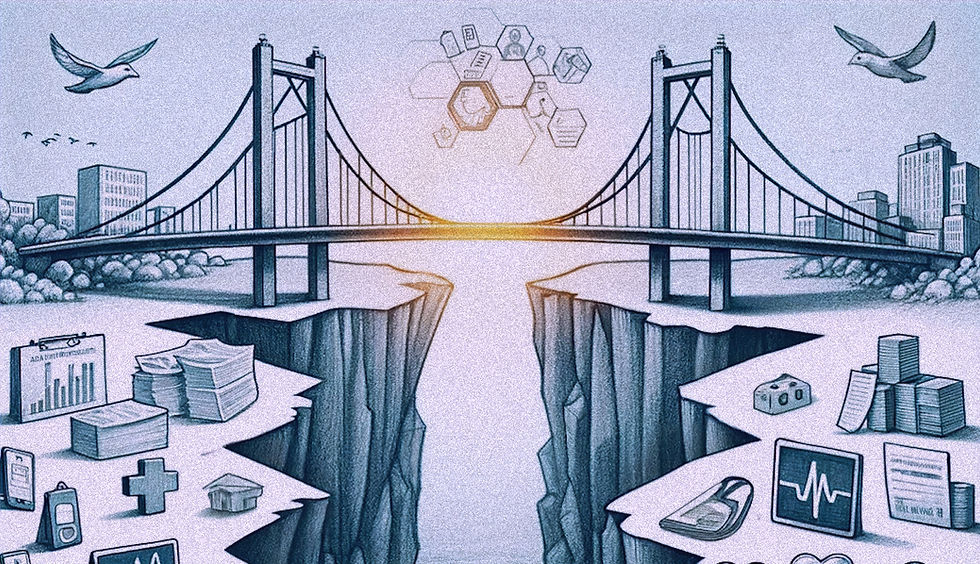

Clinicians and consumers know only too well that life circumstances such as poor housing, income and food insecurity can have a negative impact on health outcomes. Conversely, participation in community activities, social connection and access to nature parks and leisure facilities can help maintain health and wellbeing.

The interplay between what is going on in people’s lives and their health status has been long acknowledged globally. Recognising that primary health care is the key to the attainment of “Health for All’, the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration was a seminal development. At its heart, the Declaration recognised that health is enabled or inhibited by social and economic circumstances.

Loneliness epidemic and COVID putting the spotlight

More recent phenomena in public health have also focused us on the health and social care connection. In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by a massive 25% according to WHO, with young people and women worst hit. Similar impacts were found in Australia. Stress factors such as the sudden loss of employment and social interaction, moving to remote work or schooling, and the impacts of sudden, localised ‘lockdowns’ to prevent further outbreaks were triggers of increased psychological distress.

And loneliness is being described as our latest epidemic with chronic loneliness inked to a myriad of health problems and earlier death. A recent report found one in four Australians say they feel persistently lonely, and that loneliness costs $2.7 bn a year in health costs alone.

We know 26% of our practice’s patients over 65 suffer moderate to severe loneliness. The challenge is what we do because we don’t have a systematic social prescribing scheme. And I do think we need a minimum data set, and we need to incentivise people to collect that information…. If we can start to aggregate this data at a practice level, we can think about the way we design our workflow and how we do our care plans.

Dr Paresh Dawda, Next Practice, GP leader and adviser

Screening for the drivers of health

Screening for the drivers of health allows primary care providers to understand the social and economic circumstances that affect their patients’ health. It is also an initial step in addressing those needs but, in this regard, Australia lags other countries with similarly advanced health systems.

According to a 2024 Commonwealth Fund Mirror Mirror report, which compares the health performance of several countries, only 13% of Australian primary care providers (or other personnel in the practice) usually screen or assess patients for one or more social need – the third lowest in the OECD.

Start with primary care

There’s need and much scope to invest in general practice capacity to respond to the social determinants of health (SDOH).

Primary care – predominantly general practices - is where most people get most of their health care and is a commonly visited health care setting. GPs and others in team have a continuous relationship with their patient and the opportunity to identify factors beyond immediate medical care that can impact on health and wellbeing.

General practice is also the setting where people with chronic diseases are managed and have their care coordinated – the very people who are at greater risk of the SDOH having a confounding effect on their health, and the group that often feel dissatisfied with medical services due to unmet social needs such as loneliness and social isolation.

General practice and PHNs: key to health and social care integration

It is common mantra for GPs and their teams to be encouraged to ask: ‘what matters to you’, not ‘what’s the matter with you’ as a way of finding out what else is going on for patients that might affect their health management and outcomes. Reforms are geared around changes to policy and funding to make multidisciplinary care more ubiquitous and to strengthen capacity for more personalised, flexible care.

With their mandate to streamline health services through linkages with primary care and allied health services and community organisations in their locations, several PHNs have made forays into social prescribing and other forms of integrated care. These foundations make general practice and PHNs critical players in health and social care integration – as potential sources of data about the SDOH, and as service developers and commissioners.

Real barriers, emergent solutions

Integrating health and social care is an exciting frontier in healthcare and was described as such by Australia’s Assistant Health Minister at a National Social Prescribing roundtable hosted by the Australian Social Prescribing Research Institute (ASPIRE).

Despite the recognition that primary care is a good place to start, the barriers are real. Practice systems, data systems with the capacity to capture information and make intelligent insights, the lack of flexible funding and the time pressures on practices are among them.

General practice is generally driven by fee for service that creates a system that means that often, despite our best efforts, the drive for volume overrides the drive to provide value for our patients.

Dr Wally Jammal, GP leader and adviser

But there are some emergent solutions. Social prescribing – an innovative approach in primary care designed to address patients’ non-medical needs by connecting people to community resources facilitated through link workers – is rapidly becoming a widely accepted practical way for primary care to make more systematic inroads into health and social care integration.

Where to start: some foundational data

A more systemic approach to collecting and using SDOH data available from general practices is a good place to start. Insights about financial distress triggered by debt and gambling, housing and loneliness and social isolation could be a minimum set of insights to gather.

Just starting to collect some data and ask the question would be useful… we don’t ask about financial distress – even if its temporary - often enough as a marker of a patient’s ability to self-manage their health generally. The other one is loneliness .. but we don’t focus on it enough because of our inability to do anything about it.

Dr Wally Jammal, GP leader and adviser

It is very evident from other countries that screening for the social determinants of health is starting to occur. But it is not being talked about in Australia….There are patient related barriers too: a reluctance to disclose, a bit of mistrust.

Dr Paresh Dawda, Next Practice, GP leader and adviser

With the right systems, cultures, incentives and referral pathways there’s profound merits in screening for the drivers of health illuminating for primary care providers the social and economic circumstances that affect their patients’ health. It is also an initial step in addressing those needs made better still if it were accompanied by a national approach to social prescribing.

A final barrier is the culture: we’ve operated for too long in a sick care model….we continue to send people back to what makes them sick in the first place, whereas if we spent an extra minute to connect them to the local community or refer them to our colleagues in the multidisciplinary team it would save us a lot of future work…. And they would stop coming back every week with the same issue which is often bio-medical.

Dr Bogdan Chiva Giurca, Clinical Lead and Global Director, UK National Academy for Social Prescribing

Benefits can be realised, and practical actions can flow from better understanding the SDOH if some selected data were to be collected through general practice.

Collecting social determinants data at the doctor patient level helps deliver what matters to the patient. At the practice level, it’s about the future workforce and building the business case to have another member of the team that can support social needs. At the system level, it’s about delivering public value

Dr Paresh Dawda, Next Practice, GP leader and adviser

There are ways to make the foray into systematic collection of SDOH less burdensome. These include software flags, adding questions into existing screens, checklists and measures such as the over 75s health check and patient reported outcome and experience measures through to the provision of financial and other forms of incentives.

It would be hard to say to the primary care system: ‘you are now going to collect data on the SDOH’ . But it may be possible to embed it systematically into something we can and are able to do by putting into place software and system enablers. If we can embed questions around the social determinants of health into PROMs that already exist as internationally validated tools, then we can show that we can collect data, how it interacts with health care needs and the patients’ own perceptions of their health and wellbeing and where we can make a difference. We can show that to patients, the practice and clinicians using hard data.

Dr Wally Jammal, GP leader and adviser

Where to start: social prescribing as part of the toolkit

General practices are not resistant to helping patients connect with services in the community to enhance their health and wellbeing. The fact is that they face difficulties in doing so. 82% of Australian general practices report that they face at least one major challenge coordinating their patients’ care with social services. These include lack of information about services in the community, lack of a mechanism to make referrals and lack of response or follow-up by social service organisations.

We find ourselves limited and hamstrung by the system. It’s often siloed, and practices are often siloed despite their best efforts to connect to the rest of the health but are very much siloed from the social system. So, we find ourselves in a very difficult bind: as clinicians we end up knowing a lot about patients wider circumstances that affect their health, but almost unable to do anything about it.

Dr Wally Jammal, GP leader and adviser

Addressing social health literacy among primary care providers and equipping them with knowledge, tools and referral pathways to play a practical role in tackling the SDOH can be facilitated by social prescribing.

Social prescribing is an innovative approach in primary care designed to address patients’ non-medical needs by targeting the broader determinants of health, including socioeconomic and psychological factors. In practice it reflects the biopsychosocial model of health at the heart of the Alma Ata Declaration, recognising the interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors in influencing health outcomes.

Central to this approach is the connection of patients to community resources—such as mental health support, physical activity programmes, and social groups—facilitated through link workers or workforce such as….social workers. By empowering individuals to actively manage their wellbeing, social prescribing provides holistic care that goes beyond traditional medical treatments, focusing on improving overall quality of life.

We’ve got a looming workforce crisis in general practice projecting ahead. Social prescribing may be part of the solution. We also have a huge variation in care outcomes based on geographical distribution in Australia. This ability to mobilise a different workforce - link worker workforce – whatever term we want to give them – particularly in remote and regional areas may help us close that gap.

Dr Paresh Dawda, Next Practice, GP leader and adviser

Social prescribing advances the quintuple aim

Striving for health equity and a workforce that is satisfied and motivated rather than burnt out are two of the quintuple aims and social prescribing can play a role in addressing all aims in primary care.

I’ve met link workers in general practice and emergency medicine environments. It’s truly rejuvenated my desire to continue working as a clinician. It’s making the team happier because we no longer send the patient home to what made them sick in the first place. We finally have a tool in our toolbox ….it prevents that moral injury that clinicians have been feeling.

Dr Bogdan Chiva Giurca, Clinical Lead and Global Director, UK National Academy for Social Prescribing

It makes sense that Australia should have the policy ambition, clinical mindsets, service cultures and models of care concerned with responding to health and social care needs through integrated primary care services enabled by the right service cultures, team compositions and funding incentives.

We need to show the value and cost effectiveness of social prescribing. Nothing will happen without that. We need to embed it into the current reforms where we are talking about reforming the system to have it more patient-centredness, data driven, integrated and team based. Social prescribing fits into all those things. How could you possibly drive the system to be more patient centred if we are not addressing what matters to the patient?

Dr Wally Jammal, GP leader and adviser

This blog and accompanying vodcast is the second in theAustralian Primary Health Care Insights and Innovation Series hosted by Prestantia Health and AUDIENCED. Our third vodcast, which will air in March, will feature Associate Professor Tara Kiran, Faculty of Medicine and Fidani Chair in Improvement and Innovation from the University of Toronto and Dr Coralie Wales OAM, Lead, Community Partnerships at Wentwest. Tara and Coralie will join Dr Paresh Dawda to discuss ‘beyond engagement: strategic approaches to consumer and community involvement”.

Comments